Flap doors

Benz Wolf

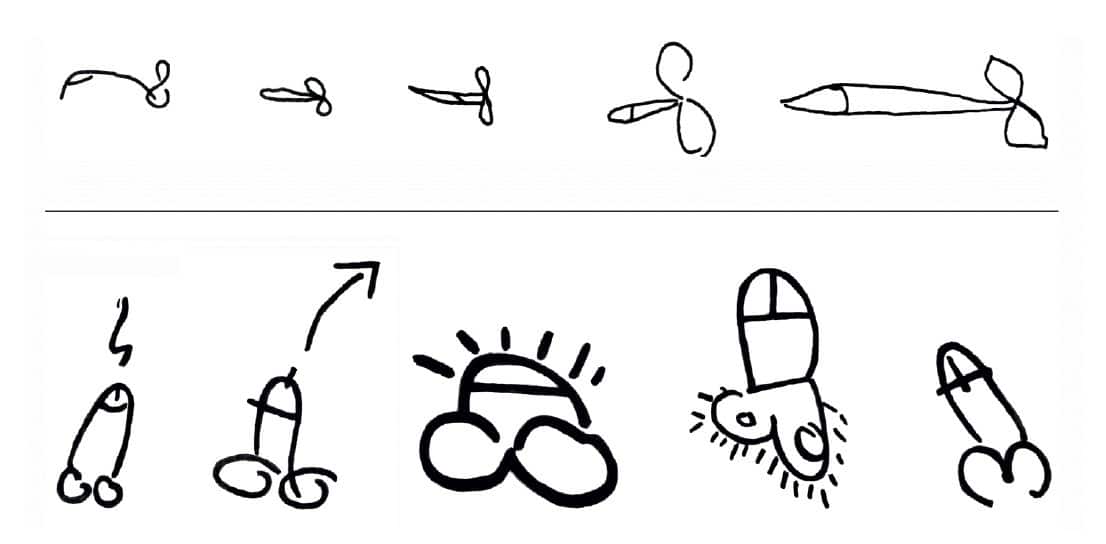

In the home of a wealthy family in Pompeii from pre-Christian times, which was excavated in 1893, graffiti can be found in the large interior. In addition to the usual numbers and rows of lines, obscenities can also be discovered. For example, the name of the postulated house owner, which may have been mentioned with friendly intentions, has been characterised as a "cocksucker", as Polly Lohmann explains in her work on "Graffiti as a form of interaction. Geritzte Inschriften in den Wohnhäusern Pompejis" (Berlin/Boston 2018). The researcher was able to discover two large-format carved tails, which are certainly ancient given the characteristic testicular drawing. This is quite unusual in an atrium.

Sexual organs in sexual activity (a stream of sperm flows from both tails) can, in principle, appear in many places; however, it is a transient genre that is characterised by the connection between reduced textuality and imagery. They are characteristically found at transition points between public and private spaces. In this respect, the atrium is a particularly unusual place.

Today, we expect to see such carvings and graffiti on public transport, school desks, lecture theatre benches or in public toilets: the latter were also places of these representations between public and private in antiquity.

<img src="“https://www.iwwit.de/wp-content/uploads/Graffiti-als-Interaktionsform_2.jpg“" alt="“Graffiti" als interaktionsform“ />

(Atrium wall Pompeii/House of the Silver Wedding; in: Polly Lohmann, Graffiti as a Form of Interaction. Berlin: De Gruyter 2018: 234/Fig. 65)

It is only the Volcanic eruption of 79 AD. It is thanks to the fact that these scribbles have been documented or handed down at all. Because these text-image arrangements are not considered art, they are not conserved and preserved, but disappear with the disposal or renovation of the surfaces on which they were illegitimately scratched, inscribed or applied. This is still the case today.

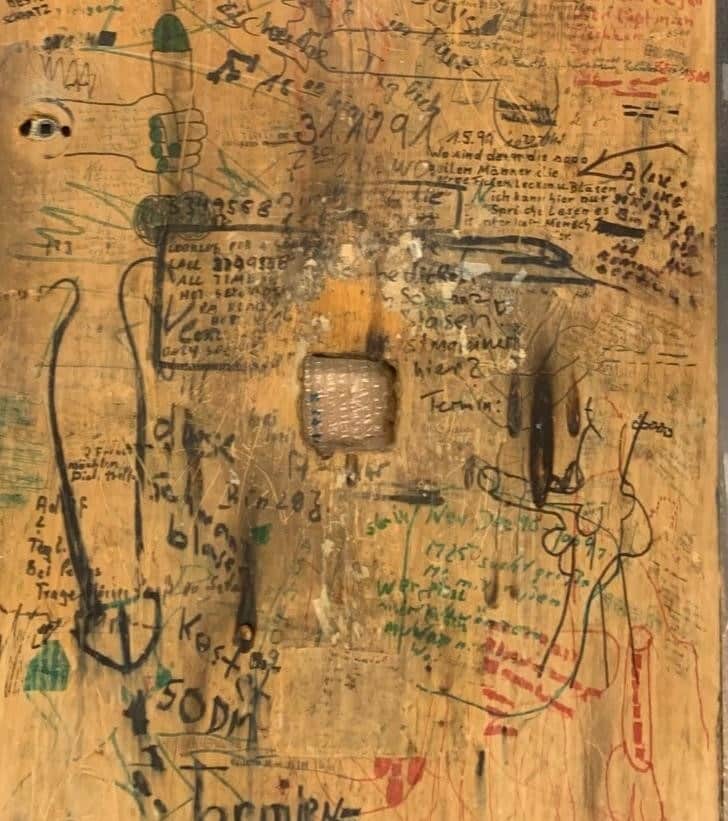

Before the public sector also gave up the business of public sanitation and privatised it, so that now self-cleaning public toilets are used by 'Street furniture makers' Since their origins in the German Empire, toilets have not only offered space for spontaneous image-text legacies, but often also linked them to forms of sexual interaction. Wooden toilet doors, which are easier to carve and write on than tiles or walls, played a special role in this and, as a three-dimensional body, also recognise an inside and an outside.

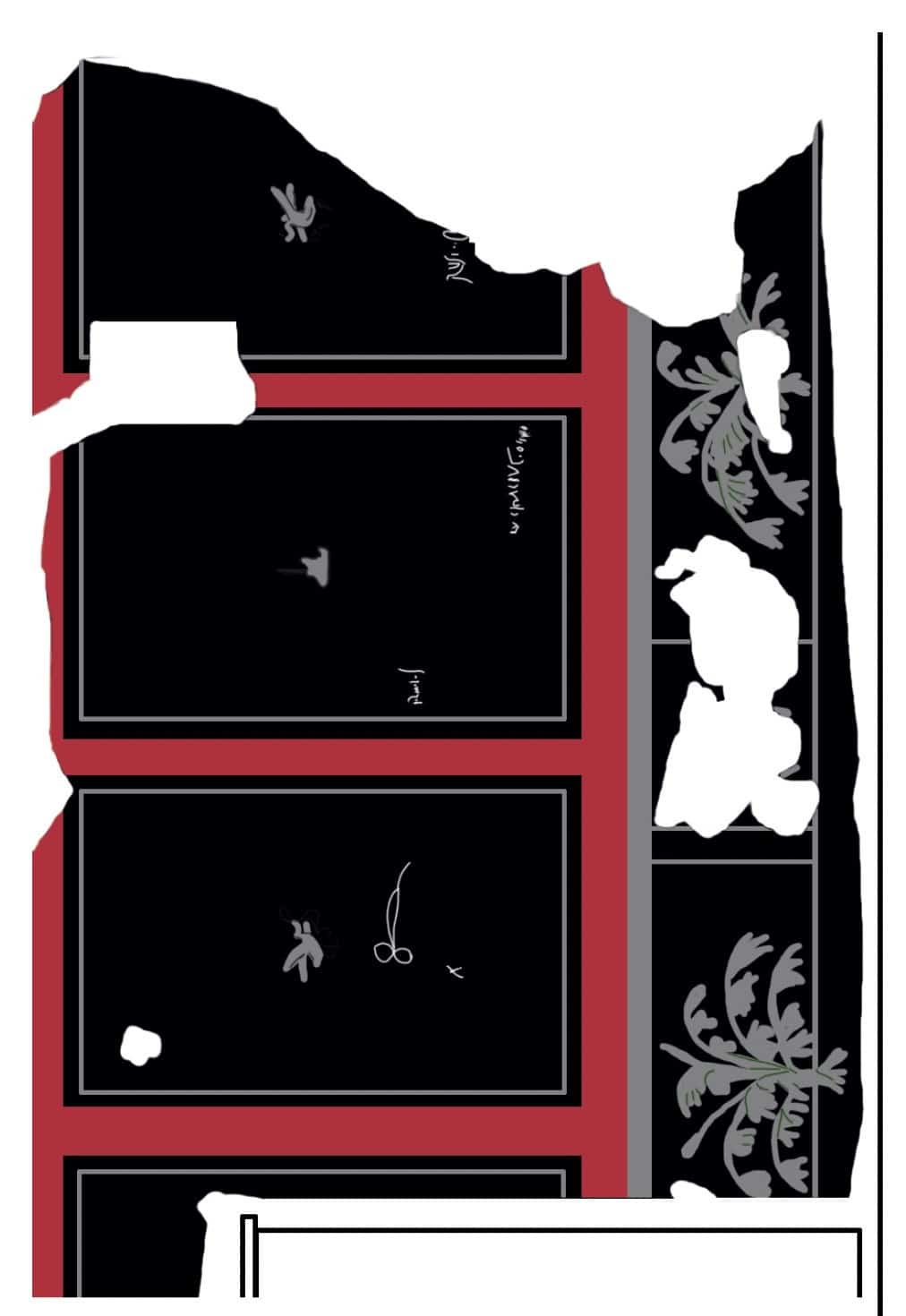

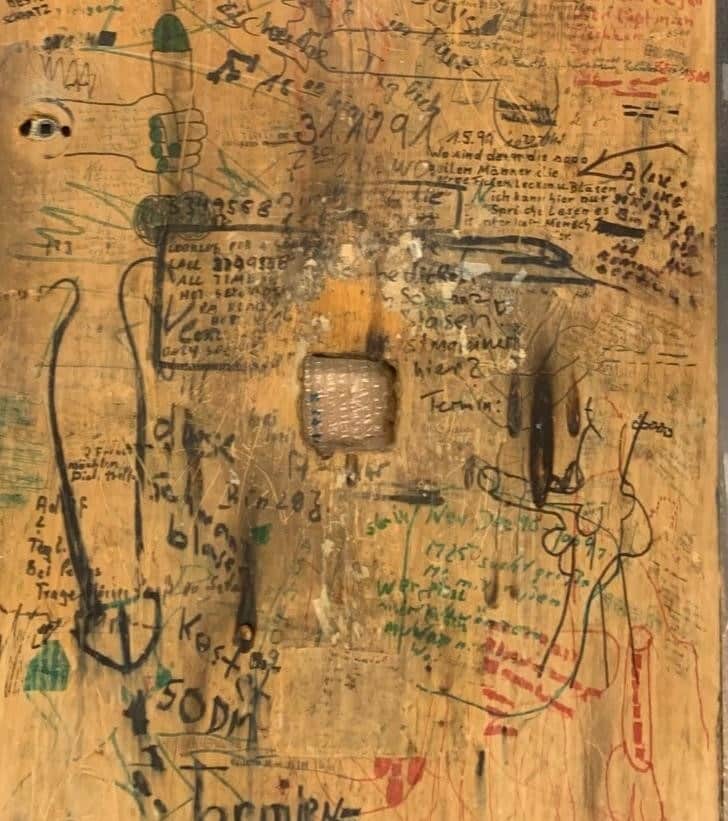

(Doors from a Berlin "Klappe", n.d., Archive Schwules Museum Berlin)

The archive of the Schwules Museum Berlin holds two impressive flap doors, the study of which is informative for an understanding of flap culture. They were discovered as part of Marc Martins exhibition Window to the loo. Public Toilets & Private Affairs (Schwules Museum, 2017/18) and are illustrated in the German-language catalogue of the exhibition, which is unfortunately out of print.

If the two sides of the door leaf are viewed as surfaces, it quickly becomes clear that the two-dimensional view must be fundamentally wrong here. The individual graphic elements can be traced back to a multitude of hands that have worked on the wood of the door leaf at different times, i.e. overlapping each other. Even where there is no overlapping, the surface can only be thought of as a layering of transparent time slices. The multitude of hands manifests itself concretely in handwriting, which can be rediscovered in various places, and in different writing tools (biros, felt-tip pen, etc.). In addition to the inscriptions, however - as in ancient graffiti - graphic elements are carved into the wooden surface. This inscription into the material exhibits various degrees of aggressiveness. There are shaves that not only make the text unrecognisable (this also occurs), but also physically remove it and then overwrite it again. The material is also injured and pierced. One impressive example is a hole in which a cigarette butt is still stuck, which seems to point to an almost sadistic relationship with the flap door. Finally, both doors are also perforated. While one door has a smaller hole in the lower centre, the other door has a large square hole in a similar position and an additional smaller one at head height. The holes clearly refer to the use that materialises on the door with the two holes on the surface. The bodies, which are characterised by the lower larger hole as glory hole and from the upper as peephole have not inscribed themselves into the wood surface (as in the case of the many inscriptions), but have lubricated - and thus made the inscriptions directly around the holes unrecognisable.

(Doors from a Berlin "Klappe", n.d., Archive Schwules Museum Berlin)

The aesthetics lie in the pictorial elements that want to be seen beyond the linguistic messages: Genitals, especially dicks, but also perspectivised bodies, each clearly identified as male or female. In the latter case, there is a contrast between what is depicted on the door and what is presumably hidden behind the door. This is an important part of the aesthetics of the flap. It is about Public spaces of non-sanctioned homosexual interaction, which is in tension with the values of the Public.

Flap poems are well known in literature. They sometimes play with vernacular forms, such as those found on toilets not used as flaps, or utilise the technique of parody, as in this case of a poem from the anonymous pornographic poetry collection The brown flowerwhich was probably privately printed in 1929. The poem parodies Ludwig Uhland's The chapel:

BALLADE

The rotunda stands above,

gazes silently down into the valley;

Mr Government Councillor Lutschmunde

presents on and off there.

The happy travellers also step

sometimes enter the temple,

to pray in front of the black wall

after drinking beer and wine.

Like a pious Eremite

the correct man bends down

to the proud centre of the Kömmling,

who can't pee for pleasure.

When the ritual is finished,

the hiker left his juice;

and, looking upwards,

he thinks: That's amazing!

(Source: Kleine Sehschule; from Polly Lohmann, Graffiti als Interaktionsform. Berlin: De Gruyter 2018: 235/Fig. 66)

Oliver Fassnacht's poem Love only exists in the cinema from (1997 in the anthology Oh bloke, I can't get you out of my head published), on the other hand, gives the appearance of an occasional poem:

Love only exists in the cinema

Fritz is one of the boys,

which are available for fifty marks.

But he does it standing up.

Short quickies on the flaps

are just small bites for Fritz.

He always gets a hard-on.

But if you take him to your room

with music and candlelight,

he will like that very much,

his arse, however, the plump one,

crisp and all-round beautiful,

you will have to pay extra.

His name is Fritz, not Valentino:

Love only exists in the cinema.

(Oliver Fassnacht)

However, the flap and the flap door can also be found in narrative texts. In Felix Rexhausen's novel, which was completed in 1964 but not published during his lifetime Fence work a conversation between two gay men leads to a cascade of memories for one of the two interlocutors, which manifests itself in the text in a litany of flaps: "How many such urinals had he not been in! Under the ground, above the ground, large urinals, small urinals, brightly tiled walls, walls coated with tar, round basins with partitions, square basins, no basins, no partitions, tiny red brick houses, black tin huts, railway station toilets, street urinals in Paris", and so it goes on for more than one page of the book. In this litany of flaps, one memory in particular stands out: "A urinal with a broken lamp and teeming with men, all reaching for each other without seeing each other, touching and fiddling with each other, a faint glow of light from the door, damned people in a cave". Damned people in a cave who can't see anything, but who are grasping at each other while there is a glow from the door - is it too far-fetched to want to recognise a proximity to Plato's allegory of the cave here? Whether it is the allegory of the cave or not, the flap door is obviously ascribed a function of potential knowledge and potential redemption from damnation (although the damned are perhaps not too desperate for redemption).

Does the flap door have a cognitive function, even a function of mediating redemption? Recognition and mediation are certainly important moments in the multiple valve, relay or even flap function that flap doors fulfil: On a first level, the flap door separates and mediates spaces: it separates the flap from the rest of the public or the cabin from the rest of the flap. It is never the case that the separated and mediated spaces form opposites (e.g. public vs. private), rather the flap door mediates a gradation: a less public, somewhat more private space is separated from the public space.

On a second level, this is contrasted by what at first glance appears to be a harsh separation, which is also conveyed by the flap door. The flap is not the public toilet in general, but the men's toilet, the space of male homosociality, which seems to be a prerequisite for the possibility of male homosexual behaviour. The flap has gender segregation as a prerequisite. Jacques Lacan has emphasised in this sense that "occidental[] man [...] subjects his life to the laws of urinal segregation". He introduces this urinal segregation as an example of the intervention of the signifier in experience and illustrates this with an image of two identical doors that are distinguished solely by the inscriptions "HOMMES" and "DAMES".

Image source: https://lacan-entziffern.de/hommes-dames-1/)

Urinal segregation is a prerequisite for what happens on the flap. It demarcates a homosocial space in which those protective devices are softened that restrict confrontation with sexuality that is always thought of as heterosexual in public (beyond the flap). Urinal segregation separates the sexus and lets the sexus take the reins.

What is striking about the flap doors of the Gay Museum, as mentioned above, is that the spaces created by urinal segretation by no means exclude a reference to femininity. The central hole of one door is clearly interpreted as a male anus by the drawing with the genitals visible beneath it. In the other door, however, the analogue hole is clearly interpreted as a vulva, this time marked by the visible breasts, among other things. Fantasies about sex with women also play a role in the labelling ("Whose girlfriend is horny to be fucked and who wants to take my balls in their mouth?"). On this level, too, the flap door has a complex function of regulating access to a male homosocial space via urinal segregation, in which the feminine remains present: as an imagined feminine, but possibly also as the tangible female parts of the subjects whose bodies move through the urinally segregated space. Images and symbolisations of femininity intervene in the sexual experience and indicate that the flap is not simply a place of gay sexuality, but a far more complex space of sexual encounter.

This complex function of separating and mediating the demarcation of spaces, in which that which has been demarcated reappears, can also be found on other levels. For example, the flap door quite specifically separates bodies from one another: for example, the body of the person in the cubicle from the body of the person standing in the anteroom, at the urinal.

The flap doors of the Gay Museum now show impressive traces that speak of mediation via the separating door: Holes through which body parts can be pushed, through which glances can be cast. Indeed, the door leaf becomes recognisable not only as a two-dimensional relay, but also as the actual three-dimensional corpus when the sexual body is depicted on it. The mediating relay becomes recognisable through its use as a mediating body.

Finally, the flap door can be focussed on in another dimension of mediation. Measured against the hygienic function superficially ascribed to it, it was ultimately diverted from its purpose as a flap door and archived and exhibited in the Gay Museum. On one of the two flap doors, the step out of the flaps can be traced in concrete terms. At the bottom right, something like a provenance notice is clearly legible: "I took this door on 12.1.93 at 600 I hung out in the hatch at Platz der Luftbrücke and dragged it home."

The flap door is taken out of its practical context and placed in a new context. Through this (in all likelihood quite laborious) step, it is historicised and ultimately musealised. It becomes a medium that mediates us, the viewers, with its time. But it also becomes an artefact that develops an auratic effect in this second misappropriation. The viewer can hardly escape the material work on the hole that characterises these doors. The sexual affordance that this door body displays is only displaced in the archival context. The body of the door challenges the gaze and becomes a collective work of art.

Links

(Gay Museum Berlin):

https://www.schwulesmuseum.de/

(Pompeii):

https://pompeiisites.org/wp-content/uploads/Pompeii_DE1.pdf

(Graffiti):

(Polly Lohmann):

(Volcanic eruption of 79 AD)

https://www.geo.de/geolino/wissen/9748-rtkl-pompeji-protokoll-des-infernos

(Street furniture)

https://www.archiexpo.de/cat/stadtmobiliar/oeffentliche-toiletten-O-1541.html

(Marc Martin)

https://www.tagesspiegel.de/gesellschaft/queerspiegel/klappe-zur-lust-3909487.html

(Window to the loo. Public Toilets & Private Affairs)

https://www.schwulesmuseum.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Fenster_Zum_Klo_Press_Kit.pdf

(glory hole)

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glory_Hole

(The brown flower)

(The Chapel)

https://de.wikisource.org/wiki/Die_Kapelle

(Oh bloke, I can't get you out of my head)

(fence work)

Photo: Atrium wall Pompeji/Haus der Silberhochzeit; in: Polly Lohmann, Graffiti as a Form of Interaction. Berlin: De Gruyter 2018: 234/Fig. 65

Photo: (Doors from a Berlin "Klappe", n.d., archive Gay Museum Berlin)

Photo: Atrium wall Pompeji/Haus der Silberhochzeit; in: Polly Lohmann, Graffiti as a Form of Interaction. Berlin: De Gruyter 2018: 234/Fig. 65

Photo: (Doors from a Berlin "Klappe", n.d., archive Gay Museum Berlin)