Russia is making headlines when it comes to homophobia. More and more regional governments are banning "homosexual propaganda" and gay and lesbian associations are suspected of being "foreign agents". However, state-imposed homophobia also has its good side: it is prompting many liberal Russians to take a stand.

Russia is making headlines when it comes to homophobia. More and more regional governments are banning "homosexual propaganda" and gay and lesbian associations are suspected of being "foreign agents". However, state-imposed homophobia also has its good side: it is prompting many liberal Russians to take a stand.

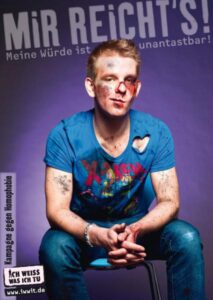

Coming out can be fatal. Just like in Volgograd. On 9 May, the body of a 23-year-old man was found in the southern Russian city: his skull smashed, his genitals injured. Apparently the perpetrators had raped the man with beer bottles. The police arrested two men aged 22 and 27. They are said to have killed the teenager after he came out as gay during the celebrations to mark the end of the war on 8 May. According to the police report, the perpetrators claimed that the victim's "patriotic feelings" had been hurt.

Heavy fines for "gay propaganda"

Patriotic feelings? That sounds strange to German ears. But in Russia, homosexuality is currently a matter of national importance. The reactions to the violent excess in Volgograd were correspondingly strong. It wasn't just gay and lesbian groups that were outraged, opponents of homosexuality also immediately took a stand: "This is not the only murder in Russia," St. Petersburg city councillor Vitaly Milonov coolly remarked, adding that the media should not sensationalise the case. The case had nothing to do with the law against "homosexual propaganda" that he was pushing for.

The background: since March 2012, a regulation has been in force in St. Petersburg to protect minors from the influence of gay and lesbian information. The law made Russia's queer metropolis, of all places, the pioneer of a homophobic roll-back. Ten other regions have since passed similar laws, most recently the Irkutsk Oblast on 24 April. The Russian parliament is also currently discussing a ban on "homosexual propaganda". It is likely to be passed in the summer. The draft law provides for high fines for violations: up to 125 euros for private individuals and up to 12,500 euros for organisations. In St. Petersburg, it can be even more expensive: Up to one million roubles (around 26,000 euros) can be imposed.

Fear is spreading

"The penalties are insane," says Gulya Sultanova (38) from the queer cultural festival "Bok o bok", which has been held annually in St. Petersburg since 2008. "For a small organisation like ours, a conviction would be the end." The festival team therefore plays it safe: "We check very carefully that no minors are present at our events," emphasises Guly Sultanova. The festival has so far been a "valuable experience", especially for teenagers coming out. "Many believe that they are perverted or sick. When they come to such an open event, it almost has a therapeutic effect." But even adults are finding it difficult: cinemas and other venues are also refusing to cooperate for fear of ruin.

To make matters worse, the small gay and lesbian organisations are also coming under pressure from another side: the Russian government suspects them of espionage. Since 2012, all non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in Russia have had to register as "foreign agents" as soon as they receive donations from abroad. Many associations and foundations complain about harassment by public prosecutors, tax authorities or health authorities. This also affects large organisations such as the German Konrad Adenauer Foundation (KAS). The Russian government's goal is clear, criticises Lars Peter Schmidt, KAS Director in Moscow: "They want to get civil society, the opposition and NGOs under control as much as possible."

There have also been two raids on "Bok o bok" since March. For the queer organisation, the Putin government's new crackdown is threatening its existence. "We can't do anything without foreign donations," explains Gulya Sultanova. "So far, no Russian foundation is prepared to support us." There are local companies that sponsor the festival. But that alone is not enough to support the extensive programme. "That's the real aim of these laws: To push the lesbian and gay community back underground."

Homosexuality as a threat to traditions

The new repression ends the brief heyday of the queer subculture. In 1993, male homosexuality was legalised in Russia, and since 1999 same-sex love has no longer been considered a mental illness. The gay nightlife in huge cities such as St. Petersburg and Moscow is legendary. But with the new self-confidence came new hatred. "Many gays and lesbians now dare to come out of the cellar," says Gulya Sultanova. "They no longer want to live in secret." Sultanova has observed that many straight people react negatively to this trend towards coming out. "This reaction is intensified because the Russian government is now focussing strongly on conservative values: patriotism, faith and obedience." Homosexuality is an excellent symbol for everything that threatens these traditions.

Nevertheless, the gays and lesbians in St. Petersburg are not intimidated. For the International Day against Homophobia on 17 May they have organised a demonstration on the central field of Mars. The so-called Rainbow flashmob has already become a tradition in Russia. The first one took place in 2009. In 2012, around 100 participants took part in St. Petersburg and released colourful balloons as a sign of the diversity of people - just like demonstrators all over the world. For 2013, 70 actions in 38 countries have been announced.

Homophobia comes to light

One of the inventors of the flash mob is Wanja Kilber. The 32-year-old moved to Germany from Kazakhstan 15 years ago. Today, he uses his knowledge of Russian and his old contacts to organise a lively exchange between the German and Russian communities. Despite the recent setbacks, Kilber also sees positive developments: "The laws against homosexual propaganda have achieved something that lesbians and gays could not achieve in all the years before: they attract the attention of the mass media and make the injustice obvious to many. Homophobia existed before, but now it is coming to light."

Wanja Kilber just visited St. Petersburg and Moscow at the beginning of April. "For me, these are always very ambivalent journeys," he says. "I meet people who have overcome their fear and are now fighting for their rights." Many straight people also join in. "That's a strong sign for Russia! When I see these courageous people, I just think to myself: what have they done to deserve this government?"

Event tips

To mark the International Day against Homophobia on 17 May, events have been announced worldwide, including in many German cities. An overview can be found at rainbowflash.org.

This year, young people from St. Petersburg and Hamburg will be holding discussions during the Hamburg CSD week. Date: 29 July, 7 p.m., Pride House, An der Alster 40, 20099 Hamburg, information at hamburg.lsvd.de.