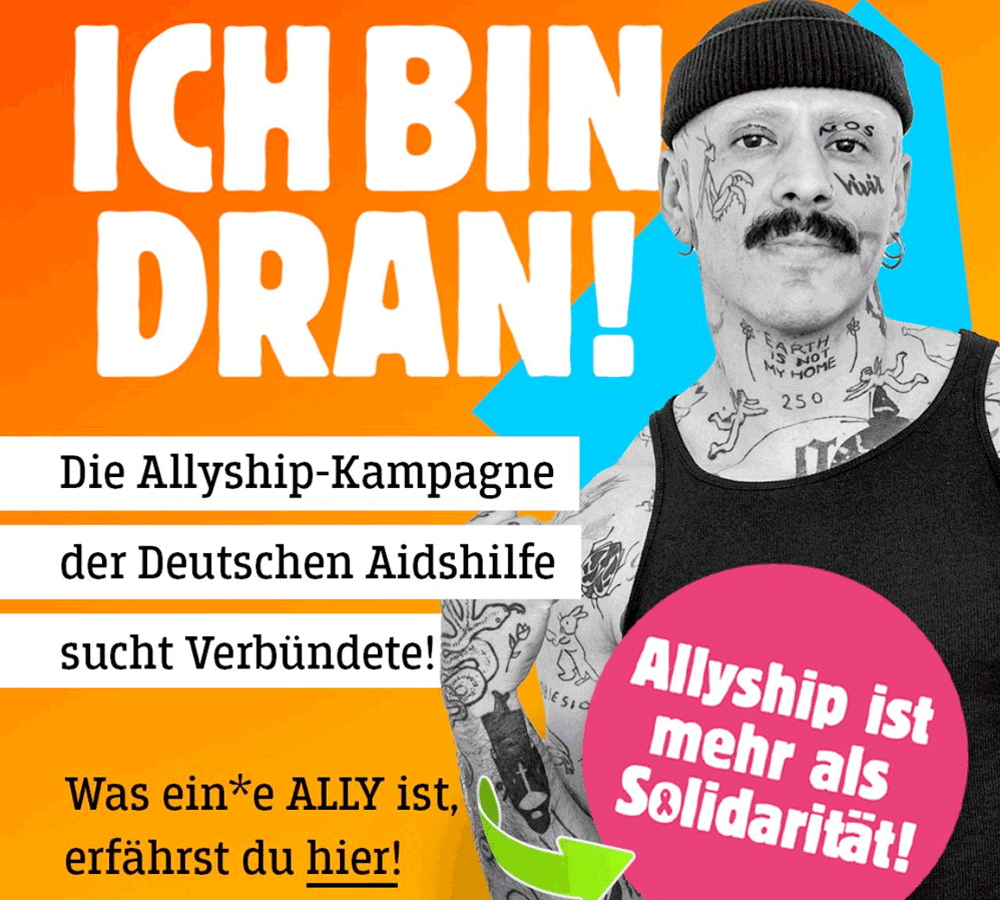

Who has what responsibility when it comes to sex? Deutsche AIDS-Hilfe has published a policy paper for discussion. The central thesis: the "criminalisation" of unprotected sex exacerbates the stigmatisation of HIV and harms prevention. [/caption]

Does an HIV-positive person have to tell their partner that they are positive before having sex? Is the positive person responsible for their partner's health if they don't want to have safer sex of their own accord? Or is it not perhaps simply a case of everyone being responsible for themselves?

These questions are always hotly debated in the gay scene. The criminal trial against ex-No-Angel Nadja Benaissa has now revived the debate in public.

On the one hand, this is about moral responsibility, on the other about the question of whether unprotected sex between a positive person and a (presumably) HIV-negative person should be punishable in certain situations - and if so, in which situations.

So far, the situation looks like this: People with HIV do not have to inform their partners about their infection. However, they must ensure protection against HIV transmission, for example by using condoms. Otherwise, they could be charged with (attempted) assault or dangerous bodily harm. However, this does not apply if the partner is aware of the infection and both agree to refrain from safer sex.

The positive person is therefore judged on whether they try to protect the other person - regardless of whether HIV transmission takes place or not.

In court and above all in the media - as the case of Nadja Benaissa shows - there is a tendency to attribute responsibility for unprotected sex solely to the HIV-positive person. Deutsche AIDS-Hilfe (DAH) has therefore now published a policy paper on the topic for discussion on its blog.

The central thesis: The "criminalisation" of unprotected sex increases the stigmatisation of HIV-positive people and at the same time harms HIV prevention:

"It creates the illusion that the state has HIV under control and that HIV-positive people are solely responsible for protecting themselves from HIV transmission." This could lead to people neglecting their own protective behaviour.

In addition: "The criminalisation of HIV transmission may lead to people not getting tested." After all, only those who know about their HIV infection can be prosecuted - some people may prefer not to do so for fear of criminal consequences and stigmatisation.

However, the working group that drew up this paper cautions that there are "certainly cases in which HIV transmission is a criminal offence, for example if the other person was fraudulently deceived, trust was exploited or infection was intended."

According to the paper, a simple rule should apply in principle when cases end up in court: Both partners have responsibility - not just the HIV-infected person. According to the authors, the positive person is not obliged to tell their partner about their infection during sex, but should - just like their partner - take appropriate measures to prevent HIV transmission.

However, the situation is slightly different if one of the partners is unable to assess the situation properly or is unable to act appropriately, for example because they are drunk or on drugs. In this case, the other partner has more responsibility.

Now former couples often end up in court. In most cases, deep wounds are involved, sometimes also the desire for retribution. Agreements on the subject of safer sex are often presented in very different ways. It is then a case of testimony against testimony and it is not possible to verify when the negative partner found out about the other's infection and to what extent he or she consciously refrained from safer sex.

The paper states: "Judges are also required to treat people with HIV impartially, i.e. not to give them less credibility per se than non-infected people. This also includes freeing themselves from the image of "irresponsible positives" portrayed by the media."

According to the DAH, such images - which have culminated in "media hunts" such as the one against Nadja Benaissa - exacerbate the stigma of HIV. However, the stigma makes it more difficult to deal openly with the infection - and therefore to handle it responsibly during sex. A statement made by Nadja Benaissa on the first day of the trial illustrates this: she was simply "terrified" to tell her partners about the infection.

The DAH also addresses another important point in its paper: HIV therapies significantly reduce the probability of HIV being transmitted. If HIV can no longer be permanently detected in the blood and no other sexually transmitted infections are present, the "viral load method" offers a similar level of safety as condoms. Shouldn't this also be taken into account more often in court?

Nadja Benaissa admitted on the first day of her trial that she had unprotected sex. The policy paper from Deutsche AIDS-Hilfe makes it clear that this is by no means the end of the story. Quite the opposite: a serious debate on the subject has yet to begin.

(Holger Wicht)

The policy paper for discussion on aidshilfe.de

Further information on the topic of criminal law at aidshilfe.de