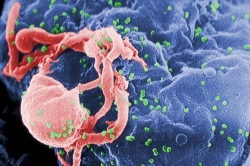

Patient no. 45 led to the trail: US researchers have isolated antibodies that can render HIV harmless in the laboratory. A breakthrough?

Numerous media, including Mirror onlinereport today on the discovery of new antibodies against HIV. The antibodies are highly effective and can stop 90 per cent of HIV viruses in the laboratory. The news is based on a report by a group of researchers from the National Institute of Health in Bethesda, USA, in the magazine Science.

What do these reports mean? Will there soon be a cure or a vaccination against HIV thanks to these antibodies?

The answer is: no. In the next few years, nothing will change in the treatment of HIV infections as a result of these research findings. However, the research group led by scientist Xueling Wu has taken an important step in basic research.

Every HIV-infected person produces antibodies. However, most of these antibodies cannot switch off the HIV virus. In addition, the virus is constantly changing ("mutating") and thus evades the attacks of the immune system. Antibodies therefore only ever match some variants of HIV.

However, there are also antibodies that can neutralise HIV. The researchers working with Wu have now specifically searched for such antibodies, specifically for variants that HIV cannot easily evade.

It works like this: The virus has areas that can hardly be changed. This includes an area on the surface of the virus that HIV uses to dock onto human cells in order to penetrate them, the CD4 receptor. This receptor can be compared to the grappling hook of a pirate ship: It always looks pretty similar - while the ships can come along very differently to disguise themselves (as a freighter, yacht, fishing boat).

Wu and colleagues have now isolated antibodies from a patient ("No. 45") that can render this grappling hook harmless in more than 90 per cent of all HIV viruses. What's more, they have managed to isolate a few of the millions and millions of immune cells from this patient that produce these antibodies.

What has been achieved with these findings? So far, it has only been possible to use the antibodies in a targeted manner in the laboratory. It would now be necessary to develop a vaccination that stimulates B cells to produce precisely these antibodies. Whether this will work is questionable and in any case there is still a long way to go. Whether such a vaccination really protects against infection would then have to be tested in a trial lasting several years with thousands of vaccinated people.

Perhaps the findings can also be used to develop drugs to combat HIV infection. Such antibody-based drugs are already being used in cancer therapy, for example.

However, in patient no. 45, the antibodies did not lead to him getting rid of HIV either.

(Armin Schafberger, Medical Officer of Deutsche AIDS-Hilfe)