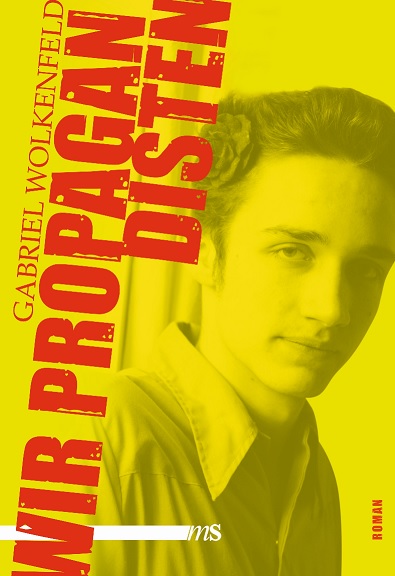

In his novel "We Propagandists", Gabriel Wolkenfeld provides a very personal insight into Russian living conditions at the time of the "homo-propaganda" law.

A small sample from the novel: "He sighs womanishly. Starts to sob. I say: Be quiet. I don't kiss him on the neck, I don't stroke his cheek. I press his head against the cold window pane. I take the prime minister from behind: I fuck Dmitry Anatolyevich Medvedev."

Curious after this passage? I knew it! But to answer the obvious question right away: No, Gabriel Wolkenfeld's debut is not about secret homosexual scandals in the Kremlin. The aforementioned Medvedev is also not really the Russian head of government, but just a look-a-like.

However, there is no reason to put "We Propagandists" aside in disappointment. Even if the book is not a novel of revelations, it is still an intimate look inside Russian living conditions in general and those of the gay and student scene in Yekaterinburg in particular.

Wolkenfeld's main character, a young German Slavicist, has moved to the city of millions in the Ural Mountains for a year to teach German at the university there. The author, who was born in Berlin in 1985, lived in Russia for a long time himself, so the snapshots of his first-person narrator's (and alter ego's?) life are probably peppered with many of his own experiences and observations.

The stay begins with a welcome from some of the men with whom the German guest has already made friends via gay networks. This is followed by an almost Kafkaesque trip through health centres and offices to collect the certificates, stamps and signatures required for the residence permit.

Sexually transmitted diseases, alcohol consumption - the guest lecturer has to provide information about everything. He is also not spared a trip to the "test centre for foreign citizens". Wolkenfeld describes the peculiarities and absurdities of the Russian soul as well as the bureaucracy with sometimes quite dry humour. "People with HIV are not allowed to stay in the Russian Federation for more than three months at a time, unless of course they have Russian citizenship," the reason for the compulsory test is explained to the German guest teacher. "But in the event that you do have Russian citizenship, you'd better do everything you can to get out as quickly as possible," says Wolkenfeld, interpreting the medical officer's explanations. "For the future of the Russian people - who would deny that? - people with HIV without Russian citizenship pose a particular security risk, especially when they stand in front of a group of young adults and explain the formation of irregular verbs."

Wolkenfeld's book may be labelled a novel, but you shouldn't expect a classically developing plot with climaxes and turning points. Instead: Flashes of the hero's everyday life, half-hearted affairs, vodka-fuelled parties in the small student flat and frustrating lessons with the students, who are completely overwhelmed by the German's relaxed teaching style. Late at night, Wolkenfeld's first-person narrator explores the scene with his friends. "Theme clubs" is the slang term used to describe such venues and bars where gay men meet in the evenings "who during the day hardly dare to stare too long at the boy's thighs on the tram. And girls who avert their eyes from the girl they love in the supermarket before their heart leaps out of their chest".

And as the year draws to a close, friendships have grown closer and amours have intensified, a rumour becomes political truth. "They will pass a law that criminalises homosexuality again," predicted Medvedev's double Mitja, but the German guest found such fears absurd. "That's not possible. They won't allow that in Europe." One of the Russian friends threatened: "If this law is passed, I'll be gone. I will not be disenfranchised". Something should be done now, "as long as we are not banned from using the word." But they lack the courage, the masses and, above all, a realistic chance of success for a popular gay uprising. Instead, they are exploring possibilities and ways to live freely abroad

On 11 June 2013, on the eve of the Russian bank holidays, the Duma finally passes a federal ban on "propaganda of non-traditional sexual relations with minors" in the second and third readings. As Wolkenfeld's first-person narrator experiences it, propaganda in favour of the anti-propaganda law is broadcast around the clock on all television channels. A law "for the protection of children. So that they don't set a bad example, don't go astray, don't settle into their misery." For homosexuals in Russia, as Wolkenfeld does not exclude, the misery - open hatred and violence - is only just beginning.

Gabriel Wolkenfeld "We propagandists". Novel. Männerschwarm Verlag, 232 pages, 19 euros