You also have to get used to freedom first. For example, "just being me. Without a disguise". In Lithuania, Algis was used to following certain rules: "You can't talk about everything. Sometimes you have to avoid your friends. You also have to be careful and not leave anything treacherous lying around. Your lies have to be perfect. And you have to choose your meeting places carefully." He had learnt to live with fear and to protect himself. As an exchange student in Germany, he now had to learn to abandon this practised behaviour: no longer constantly checking his own movements and voice in public, and always looking around carefully. However, the 19-year-old is sometimes overwhelmed by so much gay naturalness. "Everyone seems to accept it equally when gays and transsexuals lick each other naked in public at the CSD parade. That's too much even for me and really embarrassing," says Algis.

Algis is one of eight representatives of the LGBT community from Poland, Latvia, Romania, Hungary and Lithuania who are portrayed in the documentary volume "Osteuropaexpress" by Marianne Zückler. The subtitle "Narratives about freedom, love, sexuality and marginalisation" outlines the spectrum of these testimonials, but reveals little about Zückler's working method.

For her "Eastern Europe Express", the Berlin-based author conducted extensive interviews with gay, lesbian, bisexual and trans* people in these countries and used these individual fates (as well as additional researched facts) to write exemplary, but equally individual and authentic life stories.

Zückler has interwoven these first-person narratives in sections and thus sorted the statements on childhood memories, first sexual experiences, coming-out experiences, queer activism and career prospects into chapters.

Realistic insight

This requires the reader to pay attention in order to gradually form a picture of the individual characters. At the same time, it fulfils the author's purpose of highlighting the parallels and differences in the experiences and attitudes of the individual protagonists. The book thus provides Western European readers in particular with a realistic insight into the living conditions of LGBT people in these former Eastern Bloc countries, based on everyday experiences, and tells of their hopes, worries and struggles.

Some readers may recognise themselves in the experiences of coming out, searching for their own sexual identity or dealing with each other in the LGBT community. However, the protagonists also report on discrimination, persecution and oppression in a form and to an extent that is fortunately not (or no longer) known in this country.

To go or to stay?

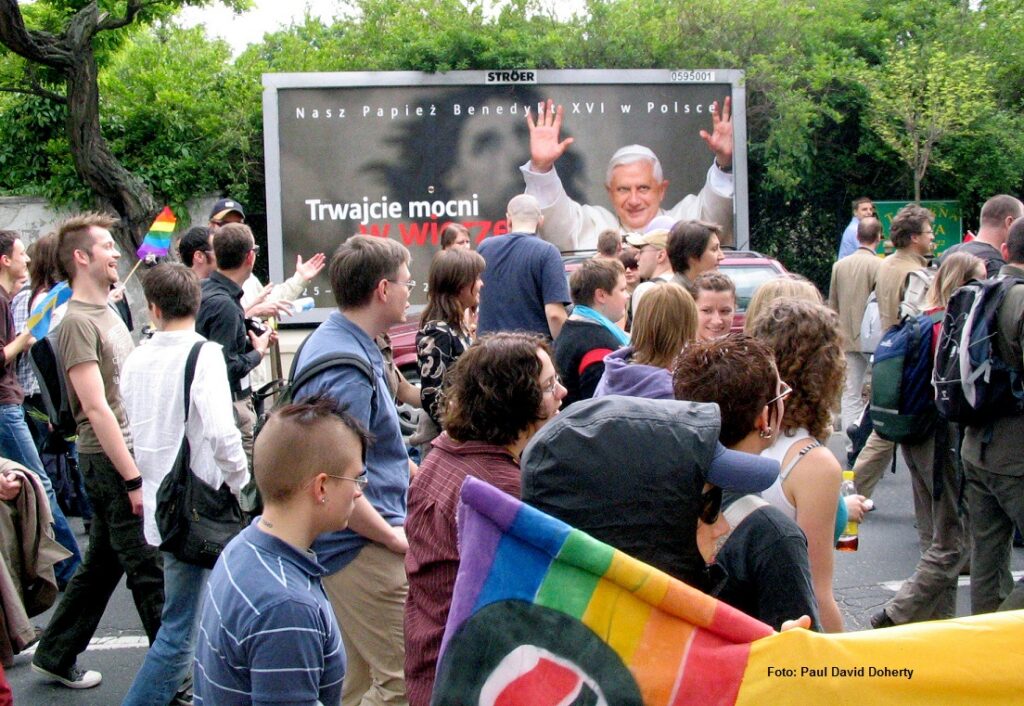

Ultimately, all of the people portrayed in the book ask themselves this question at some point in their lives, and they have very different answers to it. Kazmierz, for example, who is in his mid-forties, is angry with all those gays, lesbians and trans* people in Poland who go abroad instead of fighting for tolerance and their own rights in their own country. "How is a society supposed to develop if this generation emigrates?" he asks. Anna from Warsaw sees the living situation in her own country in a wider context. "We're not doing badly," she says. LGBT people no longer have to be afraid in Poland. "We're not persecuted like in Russia, Africa or the Arab countries. We don't disappear into camps without our relatives knowing where to look for us or whether we are even still alive." From our Western perspective, their expectations of the community sound downright sobering and defensive: "We are a minority. We have to adapt." But she believes that LGBTs can improve their situation step by step.

Algis is certain that it will be quite some time before lesbians and gays in Lithuania are no longer discriminated against and can marry or adopt children. "But the living situation is nowhere near as bad as it is portrayed in the media and forums. And Kazmierz is also fed up with this "tendency towards martyrdom". The role of victim may be easy to instrumentalise politically, but this form of self-humiliation is unbearable for him. And even worse for him is "this Western patronising attitude". Algis doesn't always want to be perceived as a "pitiable gay man from the Baltic States". For him, that is not solidarity. Kazmierz from Poland, who is in a relationship with a German, echoes this sentiment: "We are not losers or victims. We are doers. We are self-confident and creative."

What Western Europeans can learn from LGBTs from Eastern Europe

Instead of just feeling sorry for them, LGBTs in Western European countries and their organisations could perhaps even learn something from their Eastern European brothers and sisters. For example, how to deal with crises and forge alliances. For Breda from Budapest, the LGBT community is primarily there to encourage, challenge and mobilise each other. What this looks like in everyday life and in political work is reflected again and again in these eight life stories. When you look at some of the current debates, trench warfare and rifts within the German LGBT movement, you wish that Breda's actually surprising and simple realisation had been more widely acknowledged in this country.

Marianne Zückler: "Osteuropaexpress. Stories about freedom, love, sexuality and marginalisation". Europa Verlag, 240 pages, paperback, 16.90 euros.