An article by Dr Dirk Sander, Gay Affairs Officer at Deutsche AIDS-Hilfe. (Editor: Tim Schomann)

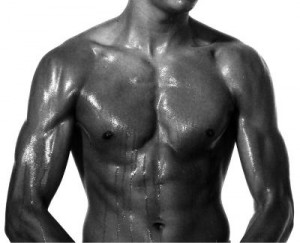

Well-trained, broad back, pronounced abs, strong shoulders: this is how "the man" is usually shown to us in gay magazines. Regardless of whether they are editorial articles or adverts. These men - usually in their twenties - are beautiful to look at, they convey an idealised image of masculinity, power and strength. Why is this image of masculinity so dominant? What is behind it and what can these images trigger?

At first glance, this seems to have nothing to do with a prevention campaign like I KNOW WHAT I DO. But if you take a closer look, it raises some questions about our attitudes and respect for each other in the so-called gay or queer community. What effects can mutual exclusion and stigmatisation have on our health well-being and our sexual protective behaviour? We want to talk to you about this!

"Faggots are pointless"

Although the image of men in gay magazines and on many a CSD truck appears quite uniform, the "queer" scene is much more diverse when it comes to physicality: fat and thin, long and short, old and young, hairy bears, chubby blokes and slim shirts, sometimes with rather soft, sometimes with striking features. Nevertheless, many people seem to be fascinated by male bodies that conform to a certain idea of masculinity; they are objects of desire. Men who are more effeminate, i.e. supposedly "feminine", are sometimes mercilessly mocked as "too gay" or rejected as sex partners on online dating portals with the comment "faggots useless". A "female" male model introduced by the Federal Centre for Health Education (BZgA) in a prevention campaign last year led to a storm of indignation in the gay social media, the model was rejected as "too clichéd" and ultimately withdrawn by the health agency due to vehement "public pressure" from the scene.

"Body image stress": Stress with your own body

The longing for masculinity is apparently great, so it's no wonder that you can find all kinds of men who are dissatisfied with their own bodies and who are prepared to do a lot to fulfil the image of the gay archetype that dominates the magazines. And there is nothing wrong with taking care of your body, doing some sport and eating a balanced diet to feel fit and attractive. However, scientific studies from recent years have found that homosexuals suffer more from dissatisfaction with their own bodies than heterosexuals. A British study on the health of gay and bisexual men from 2011 emphasised that almost half of gay and bisexual men are concerned about their appearance and also wish they had to worry less about it. Twenty per cent of respondents were bothered by their weight or eating behaviour. In another recent study, Christopher J. Hunt from the University of Sydney found that gay men are sometimes "torn" between the contradictory ideas of being muscular on the one hand and slim on the other. Psychologists refer to this phenomenon as "body image stress": They say there is a difference between "normal" body awareness and stressful dissatisfaction with one's own body. In any case, it is worth thinking about how much sport and diet control is still "healthy" and when the efforts to achieve a fit and attractive body become a stressful and therefore rather detrimental burden.

A number of theoretical considerations can be found in the literature as to why the longing for a masculine, toned body can become so overpowering in gay men in particular. On the one hand, there are certain fears of being ostracised by others as (too) gay, which is why they try to appear particularly "masculine" in the conventional sense; negative experiences could also act as an amplifier here. Shame" about one's own sexuality, which does not correspond to the social norm, could also play a role here. It is also assumed that for some, the idea of being better prepared and protected against anti-gay violence attacks with a particularly powerful male body could be a guiding factor; here, experiences of violence could also have a reinforcing effect on the desire for "masculinity". Incidentally, such experiences of violence are not uncommon. A recently published German survey by Michael Bochow and colleagues shows that around half of the gay and bisexual men surveyed have experienced verbal and physical violence. A statistical value that, by the way, has not changed in the last twenty years!

Hardly any emotional support and security in gay scenes?

Another assumption for the development of "body image stress" is that gay men may tend to have lower self-esteem due to experiences of exclusion and stigmatisation in society, and that the desire to shape a "masculine" body serves to strengthen self-esteem. Further considerations assume that the dissatisfaction with one's own body could also, perhaps as a reciprocal effect, stem from the expectations of certain body ideals from the gay scenes themselves. Phil Langer, a social psychologist at the University of Frankfurt, found in his 2009 interview study that significant support that could offer emotional and physical security was hardly to be found in the gay scenes. On the contrary, he writes that expectations regarding ideals of youthful age, masculine virility and sexual and physical beauty are clearly formulated within the gay scene(s), and that these can become individual stressors.

Some authors therefore call for more discussion in the gay and queer scenes about these backgrounds, e.g. about experiences of violence and how to deal with them, about ideals and expectations of certain forms of "masculinity", but also about the importance of respect and cohesion within the scene. Last but not least, this discussion seems important in light of the fact that some authors consider it likely that risk behaviour during sex could be encouraged by the conflict between a lack of self-esteem and the desire to appear particularly masculine.

The business of dissatisfaction

However, reflection on such connections can only be found in a few gay and queer circles. Meanwhile, the industry that set out to satisfy our needs has long since recognised our dilemma and developed a huge business out of it. The gay "gym culture" that emerged in the USA and is now also widespread here is just one example. In gay lifestyle magazines, which (partly out of ignorance, partly out of pure cynicism) promote and cement this aforementioned normative male image, all kinds of things are on offer for those who are dissatisfied with their body image. And this goes far beyond fitness programmes: in addition to Botox and other wrinkle killers, tinctures for better hair growth are offered; even "skincare lines" for men that promise "effective solutions" for firming connective tissue and "long-term" improvement of "body contours" seem to be selling. Even surgical procedures have recently been recommended. However, such radical methods of body shaping are, fortunately, only affordable for some of us.

As I said, there is nothing to be said against doing something for your fitness and appearance, thinking about a balanced and healthy diet, but it is also up to us to reflect on the mechanisms and backgrounds for efforts that go beyond this and are stressful, to establish more cohesion in the "queer" scenes and to develop composure in the face of supposed "blemishes".

That's why we want to address this topic and discuss it with you? What ideals and goals are really important to you? Where do you feel pressure to conform to a certain (masculine) image in the scene? How do you deal with it? What do you expect from a gay scene that often describes itself as a community? Does the community and cohesion (still) exist? Or is it all an illusion?

Discuss with us on facebook! We look forward to your suggestions, criticism and food for thought.

Literature

Bochow, M., Lenuweit, St., Sekuler, T., Schmidt, A. J. (2012): Schwule Männer und HIV/AIDS: Lebensstile, Sex, Schutz- und Risikoverhalten 2010. forum volume Deutsche Aidshilfe e.V., Berlin

Hunt, Ch. J. et al. (2012): "Links between psychosocial variables and body dissatisfaction in homosexual men: Different relations with the drive for muscularity and the drive for thinness." In: International journal of Men's health, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 127 - 136

Pretzel, A./Weiß, V. (eds.): Rosa Radikale. The gay movement of the 1970s. Edition Waldschlösschen, Männerschwarm Verlag, Hamburg 2012

Langer, Ph. C. (2009): Damaged identity. Dynamics of the sexual risk behaviour of gay and bisexual men. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden

Halperin, D. M./ Traub, V. (eds.): Gay Shame. Chicago/London: university press 2009

Mbody May-July 2010 www.m-body.de

Guasp, A. (2012): Gay and bisexual men's health survey. http://www.stonewall.org.uk/documents/stonewall_gay_mens_health_final_1.pdf