"We're making sex safer for everyone and the gay community healthier." This is the promise made by the organisers of the Swiss campaign "Break The Chain", which starts on the first of April.

Background: A significant proportion of HIV transmissions occur in the first few weeks after infection, when the newly infected person is not even aware of their infection, but Highly contagious due to the enormous amount of viruses are. The virus can then spread quickly in sexual friend networks. "Break The Chain" aims to break this "chain of infection" - and calls on people to only have safer sex for four weeks or to abstain from sex. The aim is to prevent new infections in Switzerland in April. This will be followed by a major test campaign in May.

The campaign was initiated by Aids-Hilfe Schweiz. On the "Break The Chain" website, short films and articles provide information about the risks of fresh HIV infections (medically: "primo infections") and describe the "revolution" that the campaign aims to start. An app for mobile phones is also intended to help. Anyone who downloads it will be asked about their sexual behaviour and given an assessment of how risky it is. Participants can then choose their commitment for the month: Will they abstain from sex altogether? Do they prefer to go jogging instead, do they only have sex with condoms? Everyone is free to make their own choice. Regular messages and tips should help them to stick to their resolutions for the month.

But how useful can such a campaign be? Is it just striking or is it really a revolution in the field of prevention?

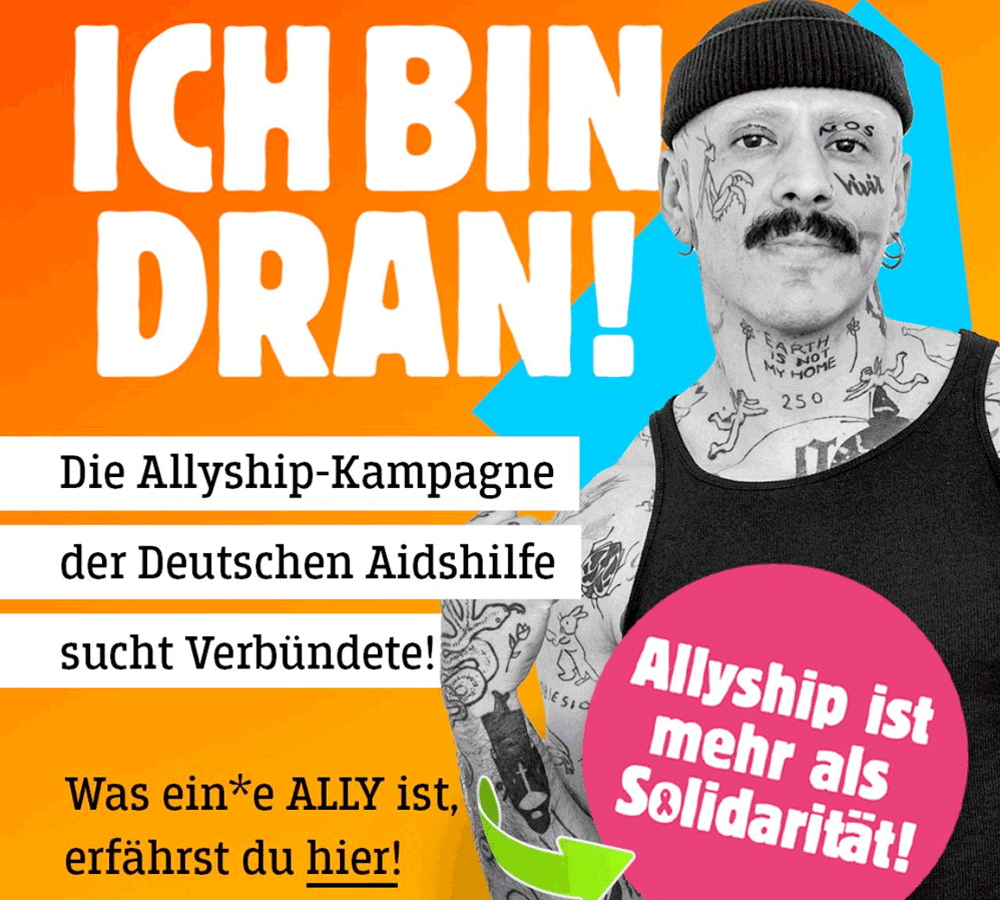

ICH WEISS WAS ICH TU (I KNOW WHAT I DO) interviewed Dr Dirk Sander, gay consultant at Deutsche AIDS-Hilfe:

The makers of "Break The Chain" hope that their campaign will bring about a "revolution". They want to break the chain of infection. Will they succeed?

The presentation of the campaign is very appealing and corresponds to certain ideas of the general gay lifestyle. The whole campaign is based on a mathematical model that is entirely plausible. If everyone behaves in such and such a way in a certain period of time, then it has such and such an effect. However, it is doubtful whether the campaign will achieve its goal, as the success of a revolution always depends on the approval of the people.

The entire Swiss gay community should either abstain from sex for a month or practise safer sex. Can this really be achieved with such an appeal?

I wish my Swiss colleagues the best of luck, but from my experience I would rather fear that the sexually active gays that the campaign is trying to address would give me the bird and would then no longer be receptive to our approaches to prevention, which are somewhat more sustainable. I have also never developed the fantasy that any of our announcements would have such a short-term impact. We are rather modest in this respect, although our successes are certainly impressive in a European comparison.

There was a similar campaign in Switzerland a few years ago. Was it successful?

According to the evaluation results, the campaign, which was carried out under the name "mission possible" in 2008 and promoted safer sex for three months, was recognised by the Swiss target group as a prevention campaign and was understood by a third of those surveyed. However, it was more likely to be approved by those who always practised safer sex anyway. Whether it had an influence on behaviour could not be clearly determined. One positive aspect was that it raised awareness of the high viral load at the beginning of the infection, i.e. shortly after infection, among many people.

What would be a better prevention strategy if the "brake-the-chain" model is not practicable?

It is practicable, but we will have to ask ourselves again whether it achieves its goals. HIV transmissions take place in a wide variety of contexts. Often, for example, due to misconceptions or assumptions, such as "He doesn't use a condom, so he's probably HIV-positive like me". Or during the infatuation phase. Sometimes there are also situations in which an otherwise constant protective behaviour is interrupted. And transmission during the primary infection phase should not be underestimated either. However, we are taking a more sustainable approach overall, trying to provide people with the best information, to strengthen them in the ever-changing trade-offs between health and a fulfilling sex life. There will always be risks in sexuality, so for us, staying negative and living positively go hand in hand. On the other hand, we also ask ourselves which structural conditions prevent health. For example, the often poor regional provision of prevention and health services, lack of access, the influence of stigmatisation and homophobic attitudes and actions. We repeatedly draw attention to such interactions between conditions and behaviour and advocate for improvements.