Illustration: Sofía Peláez

Safe or safer spaces?

The term "safe spaces" refers to mostly physical places that are free from prejudice and any form of discrimination. Historically, the emergence of this concept in the 1960s is directly linked to the history of feminism (more specifically, its second wave) and the history of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans* people. Nowadays, the term is also used to describe spaces in which other forms of disadvantage or degradation such as racism or ableism should have no place.

However, the promise of safety inherent in this word is illusory. Neither in the past nor in the present have there been spaces that were absolutely safe for their users or free from certain mechanisms of exclusion or stereotyping. For this reason, the term "safer spaces" is used today to emphasise the recognition of this fact and the active efforts to counteract persistent forms of discrimination. Both historical and current debates about queer safe spaces in Germany and possible solutions to these problems are listed below.

"Sometimes you think hell has given all the inmates a holiday": Controversial rooms in the Weimar Republic

Even though the first queer pubs and parties already existed at the end of the nineteenth century Karl Heinrich Ulrichs reported on so-called "Urningsbällen" or later "Transvestitenbällen" as early as the 1860s - they experienced a real boom during the Weimar Republic in the course of democratisation. After all, the "Golden Twenties" went down in history with their colourful, exuberant parties and famous permissiveness. The successful television series Babylon Berlin as well as Hollywood classics such as Cabaret bear witness to the immortal myth of the "Happy Twenties".

But the reality was not necessarily so colourful, not only because of the continued existence of some criminal laws such as Paragraph 175 or Paragraph 183, which mainly affected trans* people. In many German cities, meeting places for queer people were temporarily monitored by the police, and raids were not uncommon. The spectre of the police withdrawing alcohol licences was another means of exerting pressure. On the other hand, dangerous blackmailers and criminals crept into many of the relevant pubs as guests.

Moreover, even 100 years ago, several fashionable establishments that were known as meeting places for queer people - including the legendary Eldorado - were also frequented by non-queer curiosity seekers and tourists. We know that the regular clientele criticised this from Friedrich Radszuweit, the chairman of the Bund für Menschenrecht, who wrote an article about it in 1927. Women's rooms were also frequented by heterosexual voyeurs, which prompted quite a few women to stop visiting them. Berlin's (and other major cities') fame as a modern cesspool of sin thus became a curse because queer people no longer felt comfortable in some of its spaces.

However, mechanisms of exclusion were also present from time to time within our own ranks. Access to queer club and party life was primarily denied to the unemployed, sex workers and people who stood out due to their unconventional gender expression, for example "effeminate" men, who were already referred to as "aunties" at the time. Respectability, i.e. the attempt to be accepted by mainstream society through heteronormative behaviour, was the highest ideal, which also led to fierce disputes within the movement.

An anonymous author from Breslau wrote in 1921 with regard to the queer scene there that "people danced and raved like mad in the pubs" and "mean jokes were cracked", so that "sometimes you think hell has given all the inmates a holiday". As late as 1929, a reader of the magazine "Die Freundin" who lived in Duisburg cited the presence of bisexual women in the lesbian pubs in the region as the main reason why they had to close sooner or later. Biphobia was therefore already a problem in the scene back then.

Between repression and legalisation: German division

Contrary to popular belief, meeting places for queer people were not only affected by police surveillance and raids in the GDR, but initially also in West Germany. Despite the repression, a small scene with relevant venues was able to develop in several cities and some that had to close their doors during the Nazi era were able to resume operations.

The liberalisation of criminal law provisions for homosexual acts in 1968/1969 in both German states and the rise of the West German lesbian and gay movement represented an important turning point. Throughout West Germany, more and more spaces for queer people sprang up - pubs, clubs, cafés, bookshops, self-help groups, men's saunas, etc. - and there were fewer of these in the GDR. There were fewer of these in the GDR: until reunification, they were targeted by the state, which is why East German homosexuals, bisexuals and trans* people met more often than in the West in private flats and houses or as part of church working groups.

With the outbreak of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, however, this thriving culture suffered a severe setback. The associated moral panic primarily affected people, but also spaces: gay saunas in particular were demonised in the media as "HIV hotspots". As a result, many scene-goers retreated into the private sphere and the social pressure continued into the 1990s and even beyond.

Safe(r) spaces since the 1990s: current challenges

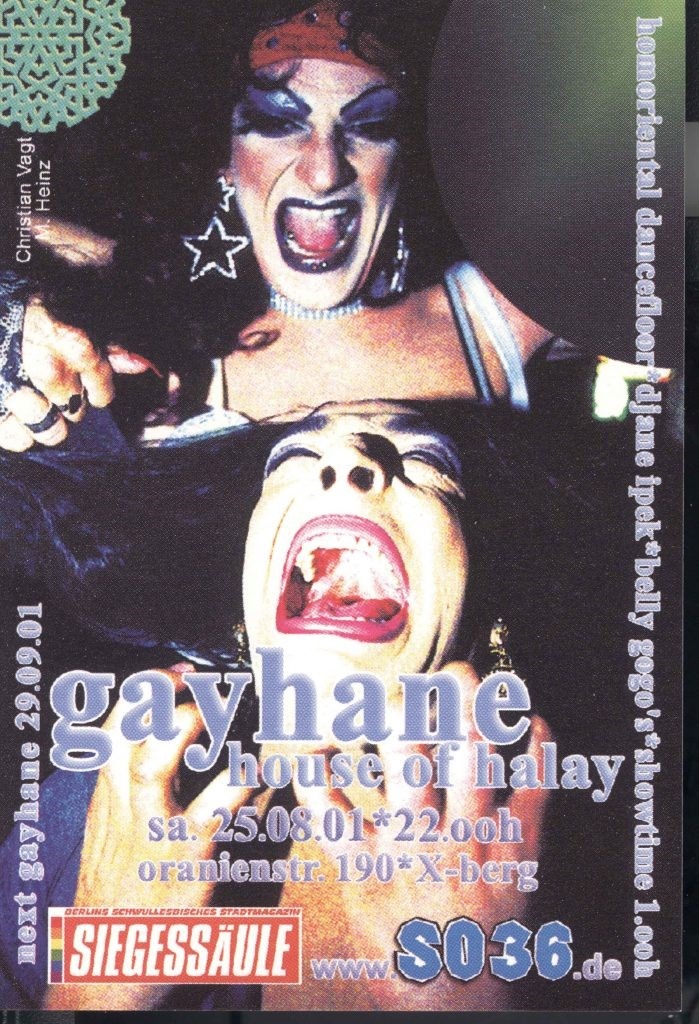

Since reunification, developments in relation to queer spaces have been predominantly positive. Their numbers have increased in many places, and the first attempts at inclusion for individual marginalised groups within the large LGBTQ+ community were made around 30 years ago. For example, the "Gayhane" party series, which still exists today, was founded in Berlin at the end of the 1990s by queer people of Turkish origin and is primarily aimed at immigrants and their descendants. The programme is constantly growing with networking opportunities, events and parties for queer people from post-Soviet countries, Latin America and Arab countries, among others.

However, the need for safe spaces for specific groups - which some would consider a regrettable fragmentation of the LGBTQ+ community - has concrete reasons. Queers of colour, trans*, inter* and non-binary people, refugees and migrants, neurodivergent people, people with disabilities and senior citizens also experience various forms of exclusion and stigmatisation within the community. Queer spaces are also not entirely free of sexism towards women. As banal as it may sound, people who are discriminated against can also discriminate against others, and LGBTQ+ people are not exempt from this.

Queer spaces do not offer one hundred per cent protection from external dangers either. Attacks on LGBTQ+ people, their meeting places and centres have been on the rise for several years now. For example: last year in particular, the Gay Museum Berlin was attacked several times, five times between February and July 2023 alone. Among other things, water bombs, food, a fire extinguisher and even an air rifle were used. Only recently, the "andersROOM" and "FLENSBUNT", drop-in centres for queer people, were also opened in Siegen and Flensburghas once again become the target of an attack.

The consequences of this state of affairs - the reproduction of -isms such as racism, trans-hostility, sexism, ableism and ageism in the community, the lack of safe spaces and the increasing violence against them - are manifold. On the one hand, it leads to those affected withdrawing more and more into the private sphere. This naturally makes the essential work of empowerment and prevention campaigns in the field of sexual health more difficult, as many are less confident about making use of the available services.

What needs to be done?

The state must be held much more accountable for attacks on queer people and spaces. Initial symbolic gestures such as the first commemoration of queer victims of National Socialism in the German Bundestag on 27 January 2023 and the travelling exhibition "gefährdet leben. Queer People 1933-1945" have been done, now action must follow. As people who were discriminated against and persecuted by the state not only during the Nazi era, but also before and after, the entire LGBTQ+ community has the right to demand more security for themselves and their spaces. The state, which has discriminated against queer people in the past and often treated them very brutally, now has a special responsibility to protect them and their spaces.

In order to actually make safer spaces safer, all -isms must (continue to) be addressed. Reflecting on one's own privileges is an important first step, but concrete action must also follow here. People from marginalised groups should be given more representation, a say and opportunities to shape things, not only in the spaces themselves, but also in leadership positions. Only in this way can their interests, concerns and perspectives be represented in the truest sense of the word and safer spaces become truly inclusive spaces that reflect social diversity.

Barriers must be broken down so that people with disabilities can also participate in community life. Possible approaches are not only offered by queer centres and safer spaces themselves: City councils such as the city of Bielefeld are increasingly taking on responsibility and developing concrete solutions, usually in cooperation with the former. The community must also become more open to intergenerational dialogue. Queer senior citizens are more often affected by loneliness and povertyBut they have been through many struggles in their lives and have invaluable life experience that we can only learn from.

Conclusion: A lesson in democracy

Overall, more space needs to be created for dialogue in both the abstract and literal sense, where people can talk about sex, sexual orientation, gender identity and experiences of discrimination. We should not be afraid of conflict or sensitive issues. Democracy and society in general thrive on - sometimes very heated - debate, provided it is conducted respectfully and without violence. Safer spaces should therefore become places for important social debates.

It is helpful to think of democracy as an ideal that can and should be practised down to the lowest level of society. So let us not only organise society democratically, but also our everyday interpersonal communication. This means having an open ear for other people's experiences, treating everyone with respect and being able to deal with differences of opinion openly. Safer spaces absolutely need a culture of dialogue, which must be strengthened.

Bibliography

- Wroclaw, F. "Police, inverts, suicides and indifferents in Wroclaw," The friendship, vol. 3, no. 26 (1921): S. 7.

- Dobler, Jens. Police and homosexuals in the Weimar Republic: On the construction of the scapegoat. Berlin: Metropol Verlag, 2020.

- Foit, Mathias. Queer Urbanisms in Wilhelmine and Weimar Germany: Of Towns and Villages. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023.

- Kenney, Moira Rachel. Mapping Gay L.A.: The Intersection of Place and Politics. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001.

- Radszuweit, Friedrich. "The perverse Berlin,ˮ The friendship sheet, vol. 5, no. 10 (1927): S. 1-2.

- Rottmann, Andrea. Queer Lives across the Wall: Desire and Danger in Divided Berlin, 1945-1970. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2021.

- Schader, Heike. Virile, vamps and wild violets: sexuality, desire and eroticism in the magazines of homosexual women in Berlin in the 1920s. Königstein: Ulrike Helmer Verlag, 2004.

- S. S. "A reply to the Rhineland girl!" The girlfriend, vol. 5, no. 23 (1929): S. 4.

- Steinle, Karl Heinz. "Pubs, bars and clubs." In: Benno Gammerl et al. (eds.): Handbook Queer Contemporary Histories I: Spaces. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2023, pp. 99-109.

- Tammer, Teresa. "Warm Brothers" in the Cold War. The GDR gay movement and divided Germany in the 1970s and 1980s. Berlin: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2023.

- Ulrichs, Karl Heinrich. Memnon. Leipzig: 1868, pp. 77-78.