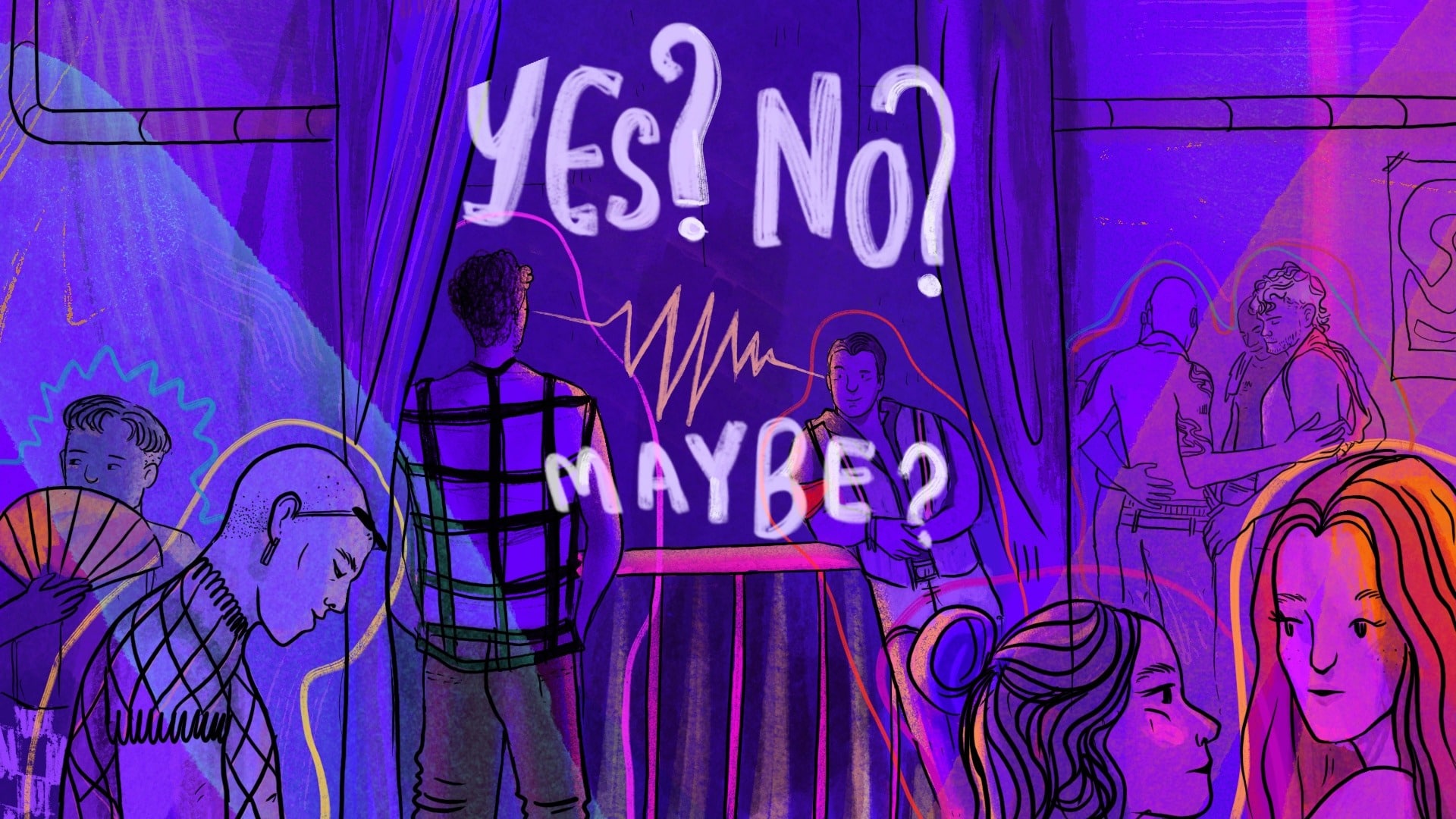

Illustration: Harjyot Khalsa, www.harjyotkhalsa.com

In Germany, any sexual act without the consent of all parties involved (affirmative consent) is a punishable offence. Affirmative consent describes a situation in which all parties involved consciously, voluntarily and actively agree to a sexual act. A sexual act could include any form of physical interaction of a sexual nature, such as kissing, hugging, touching or sexual intercourse. This consent must be clearly expressed verbally or non-verbally, can be withdrawn at any time and must not be obtained by force, coercion or manipulation. A "yes" to a particular action does not automatically imply consent to other actions, and prior consent does not automatically apply to future interactions. Silence or lack of resistance does not constitute consent. Especially when someone is unable to make clear decisions due to alcohol, drugs or health impairments, consent cannot be given. In such cases, it is crucial to recognise whether the other person is incapable of acting.

An important step in promoting affirmative consent was the introduction of the "Antioch College Sexual Offence Prevention Policy" in 1991 at Antioch College in Ohio-USA. This policy was introduced in response to growing concerns about sexual assault on college campuses and was inspired by feminist movements. It aimed to create a culture of mutual regard and respect: Consent had to be actively, consciously and voluntarily given. This policy transformed the understanding of consent, helped prevent sexual assault and created a new standard for dealing with sexual consent. This pioneering work paved the way for modern approaches in queer spaces too.

From gay darkrooms and sex-positive FLINTA parties

In these queer spaces, which are intended to serve as safe havens for people who experience discrimination due to their sexual orientation or gender identity, special care is taken to ensure that everyone involved is not only physically but also emotionally safe. Clear lines of communication are established and the individual boundaries of each person are respected. However, even within queer spaces, there are differences in how consensus is practised and implemented, which can also depend on the respective location and its circumstances.

However, if for some reason someone behaves inappropriately without respecting the consensus of others, this should not be a reason for punishment or exclusion, but an opportunity to learn from it. In a time of constant political correction, the space for punishment should be replaced by alternative approaches that promote education and personal growth. Non-binary mediator Joris Kern has been giving workshops on sexuality and consent for people working in educational fields since 2009, trying to define consent as an attitude or culture and not just a method. Joris has written two books on consent: Sex but the right way and Consensus culture. He*she also learned about the differences in queer spaces while working in the organisation team of a sex-positive FLINTA party. "It's exciting to see how the spaces and dynamics at gay and FLINTA parties differ, especially when they take place in the same venue but at different times," says Joris. At the FLINTA parties, the atmosphere was often quieter, and a lot of emphasis was placed on participants getting to know each other and communicating with each other first to create a slow sense of safety and consent before physical interactions and going into the dark room. In contrast, the gay parties focussed on physical contact. Participants moved around the room and were already able to make contact, often until someone explicitly said they didn't want to. "Both approaches have their opportunities and challenges. The gay scene could benefit from encouraging more communication during and before interactions, while the spontaneity and impulsivity in gay cruising spaces would be a strength that FLINTA spaces could capitalise on. It's important to create spaces that allow for both pleasure and spontaneity but also ensure that everyone involved feels comfortable and respected," Joris continues.

Punish or learn?

The legendary SchwuZ club in Berlin, which emerged from Homosexuelle Aktion Westberlin (HAW), is known for its sex-positive parties that create a safe and inclusive space for the LGBTIQ+ community. Their website clearly states: "Consensus distinguishes sex from sexualised violence, among other things.". David Degener from the awareness team there emphasises that consent is not a term that many people take for granted. He conveys the team's understanding that people have different backgrounds and experiences that influence their behaviour and their understanding of consent. A young person from a small village who came out at the age of 18 and wants to try out Berlin's kink parties may have less experience in queer spaces than someone who grew up in Berlin. These different socialisation conditions can lead to some people unconsciously acting awkwardly because they lack the necessary knowledge.

When a person tells the team about an unpleasant experience, they are initially believed and it is determined what this person wants and needs. Many of those affected do not know how to deal with the situation at first, as some experiences of assault only become clear after a while. "I was kissed and didn't actually say anything. I don't even know how I should deal with it," David gives as an example. The context must also be considered: If the person concerned is a BPoC, for example, and is repeatedly grabbed in the hair, it is not just a consensual assault, but also a racist assault. Such situations also occur during sexual encounters in the darkroom, where assaults can occur.

There are cases where a person's behaviour endangers other guests. Such people are taken out of the club by the team and it is explained to them why they are being taken out. "One of my first cases was about a person who was hugging other people repeatedly and without their consent," David reports. "This person, who was intoxicated, would often hold people and not let them go, despite their pleas. One affected guest often said, 'No, please don't touch me'. This person was eventually expelled and wrote us an email a year after this incident." The team does not tolerate any form of offender protection but believes that people should have the chance to learn and change. When someone is expelled from the club, the person concerned receives a card with an email address. This allows the person to get in touch with the feedback team later and talk about the case in peace. David takes the time to do this and, together with the management, is primarily responsible for replying to these emails. "It is important that there is a high level of confidentiality and that these processes are discussed. Of course, this takes a few days because I bring in all perspectives and don't want to prejudge anyone," he explains. The dialogue allows different perspectives to be brought in and topics such as boundaries, consumption and behaviour to be discussed. This dialogue could even lead to the person concerned being allowed back into the club after reflecting on the incident. "I don't want to swing a hammer and say: guilty or innocent, but rather enter into a dialogue and educate people," says David.

Joris takes a similar view, believing that sanctions or punishments are not always the best solution and that a distinction must be made between accidents and assaults. An assault occurs when someone disregards another person's boundaries and possibly deliberately tries to overstep them. An accident, on the other hand, often occurs when both parties believe that they are acting consensually but later realise that this was not the case. This can happen due to unclear agreements or misunderstandings. "A constructive way to deal with a consensual accident is to take responsibility and learn how to avoid similar problems in the future," explains Joris. "This could mean being more aware of your own boundaries, asking more questions or taking substance use into account. A well-resolved accident can even help to deepen a relationship by increasing trust and understanding." In contrast, an assault often requires distance and protection for the person involved.

Joris points out that punishment for the sake of punishment, such as exclusion as a form of revenge, is not productive. Instead, the focus should be on creating safe spaces and also supporting those who are willing to learn from their mistakes. There should be opportunities for people who have behaved inappropriately to change and understand the impact of their actions. "While safety is the top priority, it is important to combine protection with the possibility of rehabilitation," adds Joris.

Consensus as a process

This is why Joris prefers to speak of consensus rather than consensus, as a continuous process in which something new always develops and new impulses emerge that could change things. "Between 'yes' and 'no' there is also a 'maybe', and you can negotiate that. It's about creating the framework for experiments." Joris emphasises the openness in sexual encounters, whereby sometimes unexpectedly beautiful things arise when we don't strictly adhere to our ideas. This requires us to make ourselves a little vulnerable. "There is also always a beginning and a stop. A 'no' always has to be accepted, anything else is abusive. Regardless of whether the 'no' comes from someone else or is my own," adds Joris and goes on to explain that "consensus often sounds like it's black and white, yes or no, one or zero. Consensus, on the other hand, is something that evolves-what I saw as consensual five or ten years ago, I might see differently now because I've learnt more about my own needs. That doesn't mean it was wrong back then, but now I understand more about what I need and how I want to interact better with others."

Such openness and willingness to embrace new things is also reflected in the experiences David has had in his work at SchwuZ. He talks about a person in a wheelchair who went into a dark room for the first time and reported how nice it was there. Before every interaction, she was asked if everything was OK for her. "Normally she is ignored, but that evening she was kindly asked how she was doing and everything in the darkroom went smoothly. It was a new and positive experience for her." This feedback shows how important it is to create an environment of respect and inclusivity through simple questions and statements such as "yes" or "no".

Post Views: 153